Kate: In The Shore in Twilight, Risai (with good reason) is very upset about the unfairness of life and blames Heaven. The response, though kindly, is basically, “This is life. Get over it.”

The problem of evil is a constant theological problem. How does Japanese culture handle the problem? Is there more of a “accept it—move on” attitude? Does Catholic original sin resonate better than Protestant hand-wringing on the same topic?

Americans (with their very Protestant culture) have currently turned original sin or the “natural” man into a kind of idol, as opposed to a condition--something that requires obeisance. The thinking seems to be that once everybody gets on-board and agrees to wallow in the narrative of evil, utopia will follow.

It seems to me that The Twelve Kingdoms rejects this tidy solution. Instead, the thinking is, Don’t worship at the altar of original sin, even the original sin of your own guilt—it’s tacky. Utopia won’t follow. Get over it and do your job.

Thoughts?

Eugene: Japan almost seems to delight in irking its neighbors by refusing to wallow in the sins of the past. Its own sins, that is. John Dower discusses the roots of this attitude at length in Embracing Defeat.

In Buddhism, desire and ignorance lie at the root of all human suffering. This is summed up in the Four Noble Truths:

- Suffering, pain, and misery exist in life.

- Suffering arises from attachment to desires.

- Suffering ceases when attachment to desire ceases.

- Freedom from suffering is possible by practicing the Eightfold Path.

The Eightfold Path consists of pursuing and mastering the Right understanding, Right thought, Right speech, Right action, Right livelihood, Right effort, Right mindfulness, Right concentration. Right thought points back at the Four Noble Truths. This is the way the world is and it's not changing anytime soon. But two through eight are addressed through individual effort.

Pure Land Buddhism, the most popular sect in Japan, arose from the belief that there is no world that is not corrupt, so rebirth on another plane, the Pure Land, is the goal. The focus is on getting there. What it is doesn't matter much, only that it's better than here and so is worth striving for.

Angel Beats doesn't actually mention any of this specifically. But that's the road they eventually realize they all have to follow to move on.

Kate: In The Shore in Twilight, The Queen Mother of the West comes across

as a rather remote, entirely rational being. This view of heaven is far closer

to the views of C.S. Lewis--who perceived the dead as inherently disinterested in the problems of mortality--than, say, the perspective of the movie Ghost.

Kate: In The Shore in Twilight, The Queen Mother of the West comes across

as a rather remote, entirely rational being. This view of heaven is far closer

to the views of C.S. Lewis--who perceived the dead as inherently disinterested in the problems of mortality--than, say, the perspective of the movie Ghost.

Do both approaches exist in Japanese art? Remote heaven and concerned heaven? Does one approach take precedence over the other? There's always the Catholic approach—God is remote but saints are close. How does that compare?

Eugene: Heaven, in the Christian sense, is "over the horizon." This in contrast to the heaven of the pantheon, the country club where the gods hang out. Basically the rules making committee. Shows like Kamichu, Gingitsune, and Noragami have a lot of fun with the godhead as a vast bureaucracy that constantly bickers and fights like the Greek gods (when they're not partying).

Though if you play your cards right, it doesn't hurt to get one of the minor gods on your side, like Yato in Noragami. Noragami tackles both the high and the low, dealing with the dead that have remained behind because of their worldly attachments and are causing problems, and also with the convoluted politics of the pantheon (Yato made a lot of enemies in the past).

Kate: A Mormon movie--I think it was God's Army--argued

that the God one believes in is entirely determined by one's parental

figure. How was a person raised to believe authority figures should or will behave? Does the same exist here?

Eugene: It seems a weird reversal, but the West (speaking broadly) insists that society is responsible for the individual, while the East says that the individual is responsible for society ("every man is a part of the main"). This leads to a "nail that sticks up gets hammered down" mentality. But it also has the paradoxical effect of placing responsibility back on the individual.

"Self-esteem" doesn't exist in the Chinese lexicon, at least not in the way Americans use it. In China, a child's regard for herself is rarely as important as [are] stark evaluations of performance. Almost as if child-rearing were an Olympic sport, the Chinese rank children on everything from work ethic to Chinese character recognition and musical skill.

The difference in Japan is that Japanese parents spend less time in tiger mom mode. Rather, they (and society at large) set rigorous goals and expectations that children are supposed to aspire to and achieve through their own effort (ganbaru). More often than not in Japanese high school dramas, the parents are nowhere in sight, or are hanging back at a safe distance.

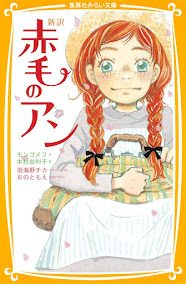

Of course, the real world might beg to differ. But it is interesting what gets idealized in our storytelling. This may explain why the spunky orphan (or virtual orphan) who rises above the lousy hand she was dealt in life is such a popular character in Japanese YA fiction.